Executive Summary

| Transparency | Replicability | Clarity |

|---|---|---|

|      |      |

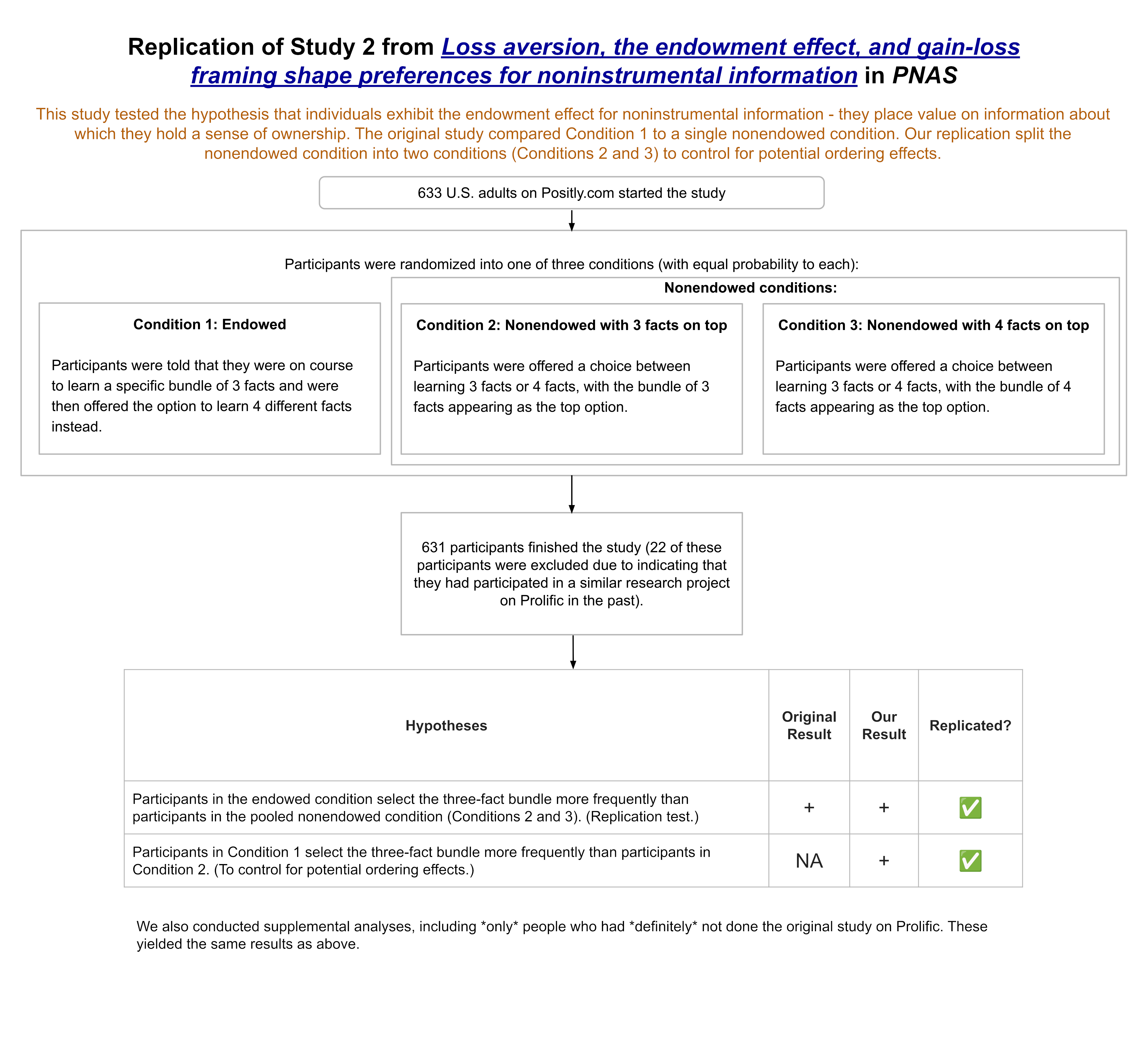

We ran a replication of Study 2 from this paper, which found that participants place greater value on information in situations where they’ve been specifically assigned or “endowed with” that information compared to when they are not endowed with that information. This is the case even if that information is not of any particular use (i.e., people exhibit the endowment effect for noninstrumental information). This finding was replicated in our study.

The original study randomized participants into two conditions: endowed and nonendowed. In the endowed condition, participants were told that they were on course to learn a specific bundle of three facts and were then offered the option to learn a separate bundle of four facts instead. In the nonendowed condition, participants were simply offered a choice between learning a bundle of three or a separate bundle of four facts, with the bundles shown in randomized order. Results of a chi-square goodness-of-fit test indicated that participants in the endowed condition were more likely to express a preference for learning three (versus four) facts than participants in the nonendowed condition. This supported the original researchers’ hypothesis that individuals exhibit the endowment effect for non-instrumental information. This finding was replicated in our study.

We simultaneously ran a second experiment to investigate the possibility that order effects could have contributed to the results of the original study. Our second experiment found that (even when controlling for order effects) there was still evidence of the endowment effect for noninstrumental information.

The original study (Study 2) received a replicability rating of five stars as its findings replicated in our replication analysis. It received a transparency rating of 4.25 stars. The methods, data, and analysis code were publicly available. Study 2 (unlike the others in the paper) was not pre-registered. The study received a clarity rating of 3 stars as its methods, results, and discussion were presented clearly and the claims made were well-supported by the evidence provided; however, the randomization and the implications of choice order for participants in the nonendowed condition was not clearly described in the study materials. Although randomization was mentioned in the supplemental materials, the implications of this randomization and the way that it could influence the interpretation of results were not explored in either the paper or supplemental materials.

Full Report

Study Diagram

Replication Conducted

We ran a replication of Study 2 from: Litovsky, Y., Loewenstein, G., Horn, S., & Olivola, C. Y. (2022). Loss aversion, the endowment effect, and gain-loss framing shape preferences for noninstrumental information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(34). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2202700119

How to cite this replication report: Transparent Replications by Clearer Thinking. (2024). Report #9: Replication of a study from “Loss Aversion, the Endowment Effect, and Gain-Loss Framing Shape Preferences for Noninstrumental Information” (PNAS | Litovsky et al., 2022) https://replications.clearerthinking.org/replication-2022pnas119-34

Key Links

- Our Research Box for this replication report includes the pre-registration, study materials, de-identified data, and analysis files.

- You can read the original paper here.

- Here, you can review the supplemental materials and the data and experimental stimuli for the original paper.

Overall Ratings

To what degree was the original study transparent, replicable, and clear?

| Transparency: how transparent was the original study? |     The methods, data, and analysis code were publicly available. The study (unlike the others in the paper) was not pre-registered. |

| Replicability: to what extent were we able to replicate the findings of the original study? |      The original finding replicated. |

| Clarity: how unlikely is it that the study will be misinterpreted? |      Methods, results, and discussion were presented clearly and all claims were well-supported by the evidence provided; however, the paper did not control for order effects or discuss the implications of choice order for participants in the nonendowed condition. |

Detailed Transparency Ratings

| Overall Transparency Rating: |     |

|---|---|

| 1. Methods Transparency: |      The materials are publicly available and complete. |

| 2. Analysis Transparency: |      The analyses were described clearly and accurately. |

| 3. Data availability: |      The cleaned data was publicly available; the deidentified raw data was not publicly available. |

| 4. Preregistration: |      Study 2 (unlike the others in the paper) was not pre-registered. |

Summary of Original Study and Results

The endowment effect describes “an asymmetry in preferences for acquiring versus giving up objects” (Litosky, Loewenstein, Horn & Olivola, 2022). Building off seminal work from Daniel Kahneman and other scholars (e.g. 1991; 2013), Litosky and colleagues found that the endowment effect impacts preferences for “owning” noninstrumental information.

Results of a chi-square goodness-of-fit test in the original study indicated that participants in the endowed condition (each of whom was “endowed” with a 3-fact bundle) were more likely to express a preference for learning three (as opposed to four) facts (68%) than participants in the nonendowed condition (46%) (χ2(1, n = 146) = 7.03, P = 0.008, Φ = 0.219). This led the researchers to confirm their hypothesis that individuals exhibit the endowment effect for noninstrumental information.

Study and Results in Detail

Methods

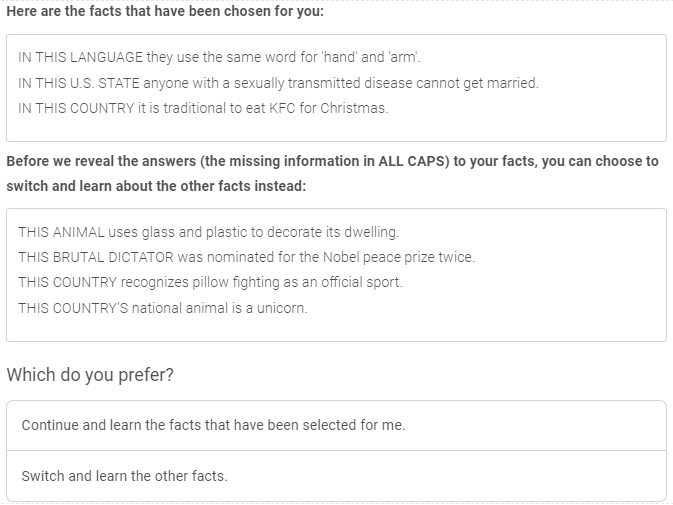

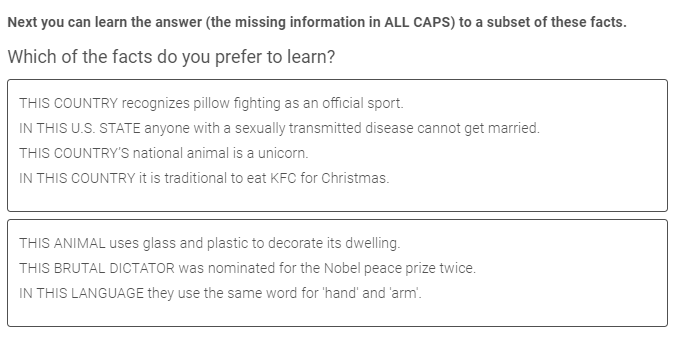

In the original study, participants were randomly assigned to one of two conditions: endowed or nonendowed. Illustrations of these conditions are shown below in Figures 1 and 2. In the endowed condition, participants were told that they were on course to learn a specific bundle of three facts and were then offered the option to learn a different bundle of four facts instead. In the nonendowed condition, participants were shown two options that they could freely choose between: the 3-fact bundle and the 4-fact one. The choice order was randomized, so the 3-fact bundle was on top half the time and the 4-fact bundle was on top the other half of the time.

None of the facts presented were of objectively greater utility or interest than any of the others. Facts related to, for example, the behavior of a particular animal, or the fact that the unicorn is the national animal of a country. Furthermore, each time we ran the experiment, we randomized which facts appeared in which order across both bundles. The subjective utility of a given fact would not be expected to affect experimental results due to this randomization process.

Figure 1: Endowed Condition

Figure 2: Nonendowed Conditions

In the original experiment, two variables had varied across conditions – both endowment and the order of presentation of the two bundles had varied. Option order had been randomized within the nonendowed condition such that a 3-fact bundle was shown on top half the time while a 4-fact bundle was shown on top the other half of the time within that condition. On the other hand, option order was not randomized in the endowed condition: the 3-fact bundle always shown on top within that condition. To control for ordering effects, we increased sample size to 1.5 times our original planned size and split the nonendowed condition (now double the size it would otherwise have been) into two separate conditions: Conditions 2 and 3.

Our participants were randomized into one of three conditions, as described below:

- Condition 1: Endowed – Participants were told that they were on course to learn a specific bundle of three facts and were then offered the option to learn four different facts instead.

- Condition 2: Nonendowed with 3-fact bundle displayed on top – Participants were offered a choice between learning three facts or four facts, with the bundle of 3 facts appearing as the top option.

- Condition 3: Nonendowed with 4-fact bundle displayed on top – Participants were offered a choice between learning three facts or four facts, with the bundle of 4 facts appearing as the top option

When Conditions 2 and 3 are pooled together, they are equivalent to the original study’s single nonendowed condition, which presented the 3- and 4-fact bundles in randomized order. In keeping with the original experiment, we compared the key outcome variable, preference for learning three (rather than four) facts, in the endowed condition and the combined nonendowed condition (the latter being the pooled data from Conditions 2 and 3, which together are equivalent to the original experiment’s nonendowed condition). However, we also considered an additional comparison not made in the original study: the proportion choosing the 3-fact bundle in Condition 1 versus Condition 2 alone.

The original study included 146 adult participants from Prolific. Our replication included 609 adult participants (after 22 were excluded from the 631 who finished it) from MTurk via Positly.com.

Data and Analysis

Data Collection

Data were collected using the Positly platform over a two-week period in February and March, 2024. To follow the original study, in order to detect an effect size as low as 75% of the original effect size with 90% power, a sample size of 391 would be required; however, in order to complete the additional analysis, we doubled the number of participants in the nonendowed condition (before then dividing the original single nonendowed condition into two conditions). This required data to be collected from at least 578 participants, after accounting for excluded participants, as described below.

Excluding Observations

Any responses for which there were missing data were not included in our analyses. We also excluded participants who reported that they had completed a similar study on Prolific in the past (N = 22). The latter point was assessed via the final question in the experiment, “Have you done this study (or one very similar to it) on Prolific in the past?” Answer options include: (1) Yes, I have definitely done this study (or one very similar to it) on Prolific before; (2) I think I’ve done this study (or one very similar to it) on Prolific before, though I’m not sure; (3) I don’t think I’ve done this study (or one very similar to it) on Prolific before, though I’m not sure; and (4) No, I definitely haven’t done this study or anything like it before. Our main analysis included all participants who selected options 3 or 4 (total N = 609). Our (pre-planned) supplementary analyses only included participants who had selected option 4 (N = 578).

Analysis

To evaluate the replicability of the original study, we ran a chi-square goodness-of-fit test to evaluate differences in preference for learning three facts between participants in the endowed versus the pooled nonendowed conditions. As stated in the pre-registration, our policy was to consider the study to have replicated if this test yielded a statistically significant result, with the difference in the same direction as the original finding (i.e., with a higher proportion of participants selecting the 3-fact bundle in the endowed compared to the pooled nonendowed conditions).

Results

Main Analyses

As per our pre-registration, our main analysis included all participants who completed the study and who reported that they believed that they had not completed this study, or one similar to it, in the past. We found that participants in the endowed condition selected the 3-fact bundle more frequently than participants in the nonendowed condition (71% vs. 44%, respectively) (χ2 (1, n = 609) = 40.122, p < 0.001).

We also conducted another analysis to evaluate the design features of the original study using these same inclusion criteria. Using a chi-square goodness-of-fit test, we compared the proportion choosing the 3-fact bundle in Condition 1 versus Condition 2 alone, finding again that the proportion of participants choosing the 3-fact bundle in Condition 1 (71%) to be significantly greater than the proportion of participants choosing the 3-fact bundle in Condition 2 (43%) (χ2 (1, n = 410) = 33.596, p < 0.001).

Supplementary Analyses

Using only those participants who reported that they definitely had not completed this study (or one similar to it) in the past, we again found that participants in the endowed condition selected the 3-fact bundle more frequently than participants in the nonendowed condition (71% vs. 43%, respectively) (χ2 (1, n = 578) = 39.625, p < 0.001, Φ = 0.26) and that the proportion of participants choosing the 3-fact bundle in Condition 1 (71%) was significantly greater than the proportion of participants choosing the 3-fact bundle in Condition 2 (42%) (χ2 (1, n = 391) = 31.716, p < 0.001, Φ = 0.285).

Interpreting the Results

The label “noninstrumental information” was used in this report to follow the language present in the original study. It should be noted, however, that some individuals might consider discovering new and potentially fun or interesting information to carry some instrumental value as it enables them to act on curiosity, learn something new, amuse themselves, or possibly share novel information with others.

We note that the proportion of participants who chose 3 facts in the nonendowed condition closely mirrored the proportion of the total facts represented by 3 (i.e. 3/7 = 43%). This is consistent with an interpretation that people might be drawn to what they believe to be the single most interesting fact and might make their choice (in the nonendowed condition, at least) based on which bundle contains the fact they perceive to be most interesting.

Conclusion

We replicated the original study results and confirmed they held when controlling for an alternative explanation we’d identified. Participants displayed the endowment effect for noninstrumental information based on their preference for choosing to learn a random 3-fact bundle that they had been endowed with, rather than a 4-fact bundle presented as an alternative option. The original study received a replicability rating of five stars as its findings replicated in all replication analyses. It received a transparency rating of four stars due to the public availability of the methods, data, and analysis code but also the lack of a preregistration. The study received a clarity rating of 3 stars as its methods, results, and discussion were presented clearly and the claims made were well-supported by the evidence provided; however, the randomization and the implications of choice order for participants in the nonendowed condition was not clearly described in the paper or study materials.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the authors of the original paper. Their experimental materials and data were shared transparently, and their team was very communicative and cooperative. In particular, we thank them for their thoughtful feedback on our materials over several review rounds.

We would also like to acknowledge the late Daniel Kahneman, a motivating force behind the original study. We acknowledge his many contributions to the fields of psychology and behavioral economics.

We would like to thank the Transparent Replications team, especially Amanda Metskas and Spencer Greenberg for their support through this process, including their feedback on our idea to add an extension arm to the study to control for the order effects we had identified as a potential alternative (or contributing/confounding) explanation for the original study’s findings. We are very grateful to our Independent Ethics Evaluator, who made an astute observation regarding our early sample size planning (in light of our additional study arm having been introduced after our initial power analysis) that resulted in us reviewing and improving our plans for the extension arm of the study. Last but not least, we are grateful to all the study participants for their time and attention.

Purpose of Transparent Replications by Clearer Thinking

Transparent Replications conducts replications and evaluates the transparency of randomly-selected, recently-published psychology papers in prestigious journals, with the overall aim of rewarding best practices and shifting incentives in social science toward more replicable research.

We welcome reader feedback on this report, and input on this project overall.

References

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149-1160. Download PDF

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1990). Experimental tests of the endowment effect and the Coase theorem. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1325-1348

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (1991). Anomalies: The endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5, 193–206.

Litovsky, Y., Loewenstein, G., Horn, S., & Olivola, C. Y. (2022). Loss aversion, the endowment effect, and gain-loss framing shape preferences for noninstrumental information. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 119(34). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2202700119