Executive Summary

| Transparency | Replicability | Clarity |

|---|---|---|

1 of 1 findings replicated |

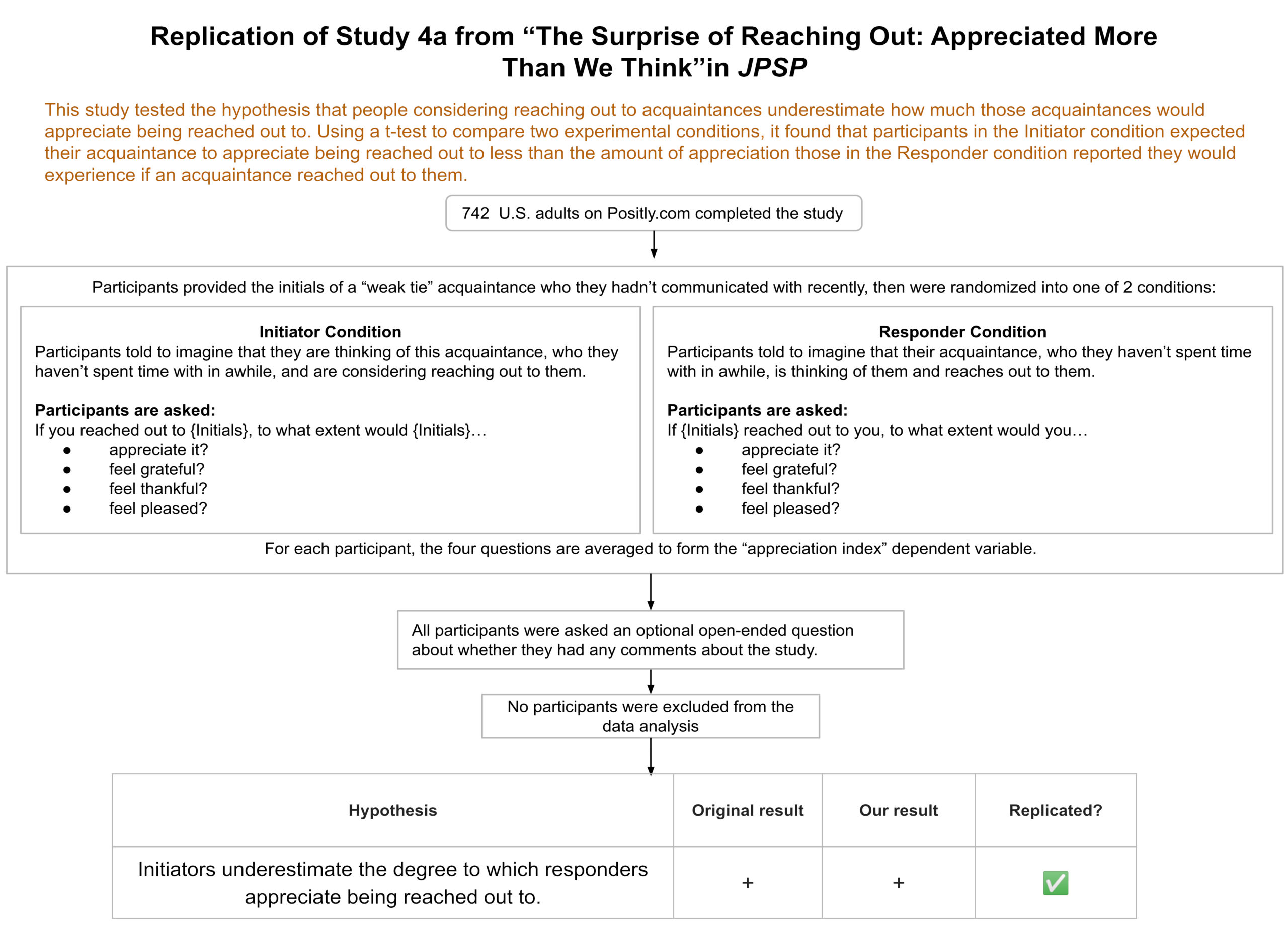

We ran a replication of study 4a from this paper, which found that people underestimate how much their acquaintances would appreciate it if they reached out to them. This finding was replicated in our study.

The study asked participants to think of an acquaintance with whom they have pleasant interactions, and then randomized the participants into two conditions – Initiator and Responder. In the Initiator condition, participants answered questions about how much they believe that their acquaintance would appreciate being reached out to by the participant. In the responder condition, participants answered questions about how much they would appreciate it if their acquaintance reached out to them. Participants in the Responder condition reported that they would feel a higher level of appreciation if they were reached out to than participants in the Initiator condition reported they expected their acquaintance would feel if the participant reached out to them. Appreciation here was measured by an average of four questions which asked how much the reach-out would be appreciated by the recipient, and how thankful, grateful, and pleased it would make the recipient feel.

The original study received a high transparency rating because it followed a pre-registered plan, and the methods, data, and analysis code were publicly available. The original study reported one main finding, and that finding replicated in our study. The study’s clarity could have been improved if the paper had not stated that the reaching out in the study was through a “brief message,” because in the actual study, the nature of the outreach was not specified. Apart from that relatively minor issue, the study’s methods, results, and discussion were presented clearly and the claims made were well-supported by the evidence provided.

Full Report

Study Diagram

Replication Conducted

We ran a replication of Study 4a from: Liu, P.J., Rim, S., Min, L., Min K.E. (2023). The Surprise of Reaching Out: Appreciated More Than We Think. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(4), 754–771. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000402

How to cite this replication report: Transparent Replications by Clearer Thinking. (2023). Report #7: Replication of a study from “The Surprise of Reaching Out: Appreciated More Than We Think” (JPSP | Liu et al. 2023) https://replications.clearerthinking.org/replication-2023jpsp124-4

(Preprint DOI: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/gxvdr)

Key Links

- Our Research Box for this replication report includes the pre-registration, study materials, de-identified data, and analysis files.

- Download a PDF of the original paper.

- Review the supplemental materials and the Research Box for the original paper.

Overall Ratings

To what degree was the original study transparent, replicable, and clear?

| Transparency: how transparent was the original study? | All of the materials were publicly available. The study was pre-registered, and the pre-registration was followed. |

| Replicability: to what extent were we able to replicate the findings of the original study? | This study had one main finding, and that result replicated. |

| Clarity: how unlikely is it that the study will be misinterpreted? | This study was mostly clear and easy to interpret. The one area where clarity could have been improved is in the description of the type of reaching out in the study as a “brief message” in the paper, when the type of reaching out was not specified in the study itself. |

Detailed Transparency Ratings

| Overall Transparency Rating: | |

|---|---|

| 1. Methods Transparency: | The experimental materials are publicly available. |

| 2. Analysis Transparency: | The analysis code is publicly available. |

| 3. Data availability: | The data are publicly available. |

| 4. Preregistration: | The study was pre-registered, and the pre-registration was followed. |

Summary of Study and Results

In both the original study and our replication study, participants were asked to provide the initials of a person who they typically have pleasant encounters with who they consider to be a “weak-tie” acquaintance. Participants were then randomly assigned to either the “Initiator” condition or the “Responder” condition.

In the Initiator condition, participants were told to imagine that they happened to be thinking of the person whose initials they provided, and that they hadn’t spent time with that person in awhile. They were told to imagine that they were considering reaching out to this person. Then they were asked four questions:

If you reached out to {Initials}, to what extent would {Initials}…

- appreciate it?

- feel grateful?

- feel thankful?

- feel pleased?

In the Responder condition, participants were told to imagine that the person whose initials they provided happened to be thinking of them, and that they hadn’t spent time with that person in awhile. They were told to imagine that this person reached out to them. Then they were asked four questions:

If {Initials} reached out to you, to what extent would you…

- appreciate it?

- feel grateful?

- feel thankful?

- feel pleased?

In both conditions, responses to these four questions were on a Likert scale from 1-7, with 1 labeled “not at all” and 7 labeled “to a great extent.” For both conditions, the responses to these four questions were averaged to form the dependent variable, the “appreciation index.”

The key hypothesis being tested in this experiment and the other experiments in this paper is that when people consider reaching out to someone else, they underestimate the degree to which the person receiving the outreach would appreciate it.

In this study, that hypothesis was tested with an independent-samples t-test comparing the appreciation index between the two experimental conditions.

The original study found a statistically significant difference between the appreciation index in the two groups, with the Responder group’s appreciation index being higher. We found the same result in our replication study.

| Hypothesis | Original results | Our results | Replicated? |

| Initiators underestimate the degree to which responders appreciate being reached out to. | + | + | ✅ |

Study and Results in Detail

The table below shows the t-test results for the original study and our replication study.

| Original results (n = 201) | Our results (n = 742) | Replicated? |

| Minitiator = 4.36, SD = 1.31 Mresponder = 4.81, SD = 1.53 Mdifference = −.45 95% CI [−.84, −.05] t(199) = −2.23 p = .027 Cohen’s d = .32 | Minitiator = 4.46, SD = 1.17 Mresponder = 4.77, SD = 1.28 Mdifference = −.30 95% CI [−.48, −.13] t(740) = −3.37 p < .001 Cohen’s d = .25 | ✅ |

Additional test conducted due to assumption checks

When we reproduced the results from the original study data, we conducted a Shapiro-Wilk Test of Normality, and noticed that the pattern of responses in the dependent variable for the Responder group deviated from a normal distribution. The t-test assumes that the means of the distributions being compared follow normal distributions, so we also ran a Mann-Whitney U test on the original data and found that test also produced statistically significant results consistent with the t-test results reported in the paper. (Note: some would argue that we did not need to conduct this additional test because the observations themselves do not need to be normally distributed, and for large sample sizes, the normality of the means can be assumed due to the central limit theorem.)

After noticing the non-normality in the original data, we included in our pre-registration a plan to also conduct a Mann-Whitney U test on the replication data if the assumption of normality was violated. We used the Shapiro-Wilk Test of Normality, and found that the data in both groups deviated from normality in our replication data. As was the case with the original data, we found that the Mann-Whitney U results on the replication data were also statistically significant and consistent with the t-test results.

| Mann-Whitney U – original data | Mann-Whitney U – replication data | Replicated? |

| Test statistic = 4025.500 p = .013 Effect size = .203 (rank biserial correlation) | Test statistic = 58408.000 p < .001 Effect size = .151 (rank biserial correlation) | ✅ |

We also ran Levene’s test for equality of variances on both the original data and the replication data, since equality of variances is an additional assumption of Student’s t. We found that both the original data and the replication data met the assumption of equality of variances. The variance around the mean was not statistically significantly different between the two experimental conditions in either dataset.

Effect sizes and statistical power

The original study reported an effect size of d = 0.32, which the authors noted in the paper was smaller than the effect size required for the study to have 80% power. This statistical power concern was presented clearly in the paper, and the authors also mentioned it when we contacted them about conducting a replication of this study. We dramatically increased the sample size for our replication study in order to provide more statistical power.

We set our sample size so that we would have a 90% chance to detect an effect size as small as 75% of the effect size detected in the original study. Using G*Power, we determined that to have 90% power to detect d = 0.24 (75% of 0.32), we needed a sample size of 732 (366 for each of the two conditions). Due to the data collection process in the Positly platform, we ended up with 10 more responses than the minimum number we needed to collect. We had 742 participants (370 in the Initiator condition, and 372 in the Responder condition).

The effect size in the replication study was d = 0.25. Our study design was adequately powered for the effect size that we obtained.

Interpreting the Results

This finding replicating on a larger sample size with higher statistical power increases our confidence that this result is not due to a statistical artifact. The key hypothesis that recipients of reaching out appreciate it more than initiators predict that they will is supported by our replication findings.

There is a possible alternative explanation for the results of this study – it is possible that participants think of acquaintances that they’d really like to hear from, and they aren’t sure that this particular acquaintance would be as interested in hearing from them. Although this study design does not rule out that explanation, this is only one of the 13 studies reported on in this paper. Studies 1, 2, and 3 have different designs and test the same key hypothesis. Study 1 in the paper uses a recall design in which people are assigned to either remember a time they reached out to someone or a time that someone reached out to them, and then answer questions about how much they appreciated the outreach. In Study 1 there were also control questions about the type of outreach, how long ago it was, and the current level of closeness of the relationship. The Initiator group and the Responder group in that study were not significantly different from each other on those control questions, suggesting that the kinds of reaching out situations that people were recalling were similar between the Initiator and Responder groups in Study 1. Since the recall paradigm presents its own potential for alternative explanations, the authors also did two field studies in which they had college student participants write a short message (Study 2) or a write short message and include a small gift (Study 3) reaching out to a friend on campus who they hadn’t spoken to in awhile. The student participants predicted how much the recipients would appreciate them reaching out. The experimenters then contacted those recipients, passed along the messages and gifts, and asked the recipients questions about how much they appreciated being reached out to by their friend. Studies 2 and 3 used paired samples t-tests to compare across initiator-recipient dyads, and found that the recipients appreciated the outreach more than the initiators of the outreach predicted they would. Studies 4a (replicated here) and 4b use a scenario paradigm to create greater experimental control than the field study allowed. The authors found consistent results in the recall, dyadic field experiments, and scenario studies, which allowed them to provide clearer evidence supporting their hypothesis over possible alternative explanations.

Later studies in this paper test the authors’ proposed mechanism – that people are surprised when someone reaches out to them. The authors propose that the pleasant surprise experienced by the recipients increases their appreciation for being reached out to, but initiators don’t take the surprise factor into account when attempting to predict how much their reaching out will be appreciated. Studies 5a-b, 6, 7, and supplemental studies S2,S3, and S4 all test aspects of this proposed mechanism. Testing these claims was beyond the scope of this replication effort, but understanding the mechanism the authors propose is useful for interpreting the results of the replication study we conducted.

The one issue with the way that study 4a is described in the paper is that the authors describe the study as involving reaching out with a “brief message,” but the study itself does not specify the nature of the outreach or its content. When describing studies 4a and 4b the authors say, “We then controlled the content of initiators’ reach-out by having initiators and responders imagine the same reach-out made by initiators.” While this is true for study 4b, in which the reach-out is described as one of a few specific small gifts, it is not the case for study 4a, which simply asks participants to imagine either that they are considering reaching out, or that their acquaintance has reached out to them. The description of the study in the paper is likely to lead readers to a mistaken understanding of what participants were told in the study itself. This reduced the clarity of this study; however, the issue is mitigated somewhat by the fact that there is another study in the paper (study S1) with similar results that does involve a specified brief message as the reach-out.

In interpreting the results of this study it is also important to recognize that although the finding is statistically significant, the effect size is small. When drawing substantive conclusions about these results it is important to keep the effect size in mind.

Conclusion

This pre-registered study provided a simple and clear test of its key hypothesis, and the finding replicated on a larger sample size in our replication. The study materials, data, and code were all provided publicly, and this transparency made the replication easy to conduct. The one area in which the clarity of the study could have been improved is that the paper should not have described the type of reaching out being studied as a “brief message,” because the type of reaching out was not specified in the study itself. Apart from this minor issue, the methods, results and discussion of the study were clear and the claims made were supported by the evidence provided.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the authors for their responsiveness in answering questions about this replication, and for making their methods, analysis, and materials publicly available. Their commitment to open science practices made this replication much easier to conduct than it would have been otherwise.

I want to thank Clare Harris and Spencer Greenberg at Transparent Replications for their feedback on this replication and report. Also, thank you to the Ethics Evaluator who reviewed our study plan.

Lastly, thank you to the 742 participants in this study, without whose time and attention this work wouldn’t be possible.

Purpose of Transparent Replications by Clearer Thinking

Transparent Replications conducts replications and evaluates the transparency of randomly-selected, recently-published psychology papers in prestigious journals, with the overall aim of rewarding best practices and shifting incentives in social science toward more replicable research.

We welcome reader feedback on this report, and input on this project overall.

References

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149-1160. Download PDF

Liu, P.J., Rim, S., Min, L., Min K.E. (2023). The Surprise of Reaching Out: Appreciated More Than We Think. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 124(4), 754–771. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000402