Executive Summary

| Transparency | Replicability | Clarity |

|---|---|---|

9 of 10 findings replicated |

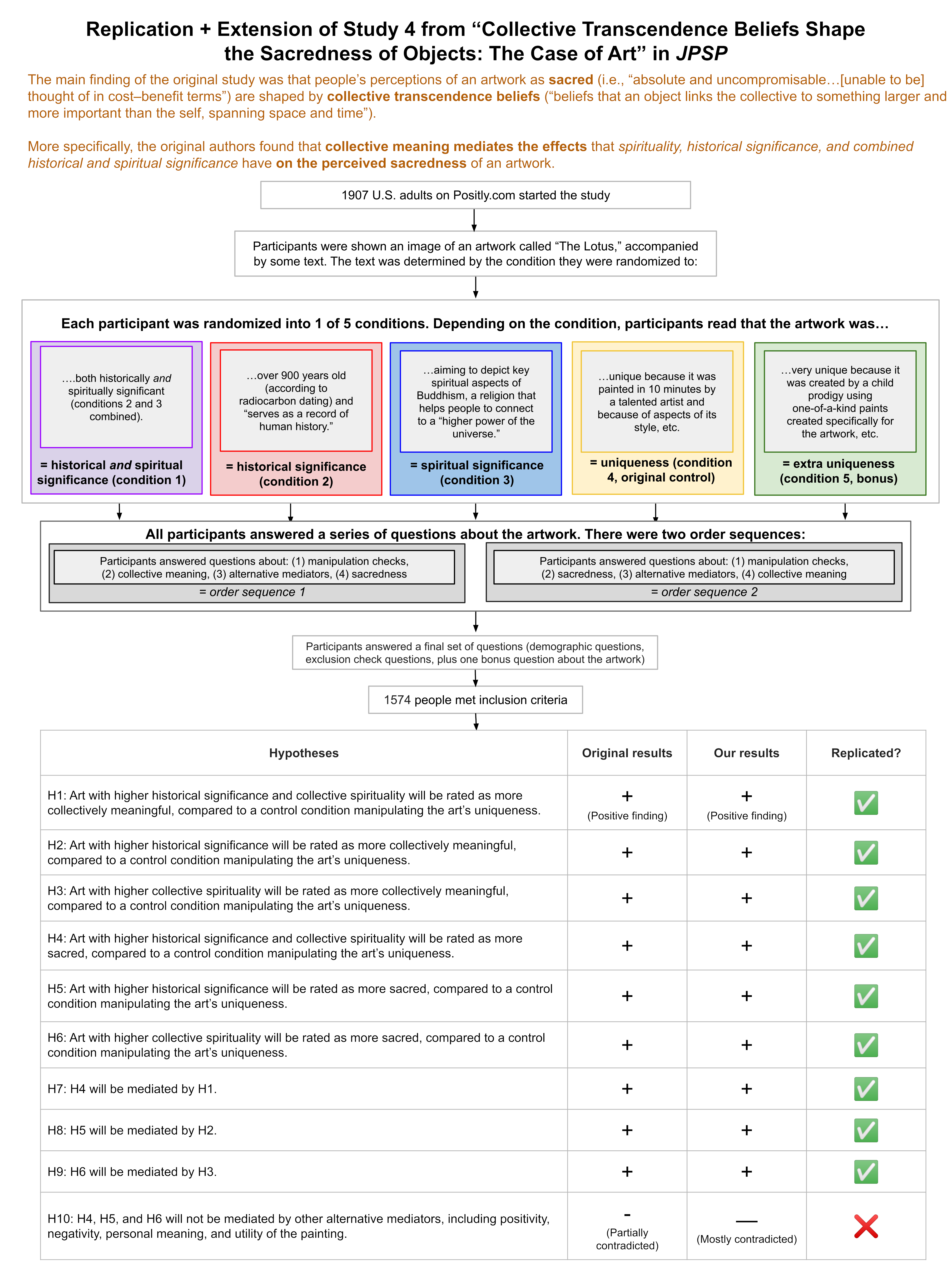

We ran a replication of study 4 from this paper, which found that people’s perceptions of an artwork as sacred are shaped by collective transcendence beliefs (“beliefs that an object links the collective to something larger and more important than the self, spanning space and time”).

In the study, participants viewed an image of a painting and read a paragraph about it. All participants saw the same painting, but depending on the experimental condition, the paragraph was designed to make it seem spiritually significant, historically significant, both, or neither. Participants then answered questions about how they perceived the artwork.

Most of the original study’s methods and data were shared transparently, but the exclusion procedures and related data were only partially available. Most (90%) of the original study’s findings replicated. In both the original study and our replication, “collective meaning” (i.e., the perception that the artwork has a “deeper meaning to a vast number of people”) was found to mediate the relationships between all the experimental conditions and the perceived sacredness of the artwork. The original study’s discussion was partly contradicted by its mediation results table, and the control condition, which was meant to control for uniqueness, did not do so; the original paper would have been clearer if it had addressed these points.

Full Report

Study Diagram

Replication Conducted

We ran a replication of Study 4 from:

Chen, S., Ruttan, R. L., & Feinberg, M. (2022). Collective transcendence beliefs shape the sacredness of objects: The case of art. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 124(3), 521–543. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000319

How to cite this replication report:

Transparent Replications by Clearer Thinking. (2023). Report #6: Replication of a study from “Collective transcendence beliefs shape the sacredness of objects: The case of art” (JPSP | Chen, Ruttan, & Feinberg, 2023). https://replications.clearerthinking.org/replication-2022jpsp124-3

(Preprint DOI: https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/cz985

Key Links

- Our Research Box for this replication report includes the pre-registration, study materials, de-identified data, and analysis files.

- The Metaculus prediction page about this study attracted a total of 23 predictions from 11 participants. The median prediction was that 5 of the 10 findings would replicate. However, participants also commented that they struggled with the forecasting instructions.

- Request a PDF of the original paper from the authors.

- The data and pre-registration for the original study can be found on the Open Science Framework (OSF) site.

Overall Ratings

To what degree was the original study transparent, replicable, and clear?

| Transparency: how transparent was the original study? | Most of the study materials and data were shared transparently, except for the exclusion-related procedures and data. There were some minor deviations from the pre-registered study plan. |

| Replicability: to what extent were we able to replicate the findings of the original study? | 9 of the 10 original findings replicated (90%). |

| Clarity: how unlikely is it that the study will be misinterpreted? | The discussion of “uniqueness” as an alternative mediator is not presented consistently between the text and the results tables, and the failure of the control condition to successfully manipulate uniqueness is not acknowledged clearly in the discussion. |

Detailed Transparency Ratings

| Overall Transparency Rating | |

|---|---|

| 1. Methods transparency: | The materials were publicly available and almost complete; not all the remaining materials were provided on request because the Research Assistants had been trained in person by the lead author, but this did not significantly impact our ability to replicate the study. We were able to locate or be provided with all materials required to run and process the data for this study, except for the exclusion procedures, which were only partially replicable. We requested the specific instructions given to the hypothesis-blinded coders for exclusion criterion #3 (see appendices), but those materials were not available. |

| 2. Analysis transparency | Some of the analyses were commonly-completed analyses that were described fully enough in the paper to be able to replicate without sharing code. The conditional process analysis was described in the paper and was almost complete, and the remaining details were given on request. However, the original random seed that was chosen had not been saved. |

| 3. Data availability: | The data were publicly available and partially complete, but the remaining data (the data for the free-text questions that were used to include/exclude participants in the original study) were not accessible. |

| 4. Pre-registration: | The study was pre-registered and was carried out with minor deviations, but those deviations were not acknowledged in the paper. In the pre-registration, the authors had said they would conduct more mediation analyses than they reported on in the paper (see the appendices). There were also some minor wording changes (e.g., typo corrections) that the authors made between the pre-registration and running the study. While these would be unlikely to impact the results, ideally they would have been noted. |

Summary of Study and Results

Summary of the study

In the original study and in our replication, U.S. adults on MTurk were invited to participate in a “study about art.” After completing an informed consent form, all participants were shown an image of an artwork called “The Lotus,” accompanied by some text. The text content was determined by the condition to which they were randomized. In the original study, participants were randomized to one of four conditions (minimum number of participants per condition after exclusions: 193).

Depending on the condition, participants read that the artwork was…

- ….both historically and spiritually significant (this condition combined elements from conditions 2 and 3 [described in the following lines]);

- …over 900 years old (according to radiocarbon dating) and “serves as a record of human history;”

- …aiming to depict key spiritual aspects of Buddhism, a religion that helps people to connect to a “higher power of the universe;” or:

- …unique because it was painted in 10 minutes by a talented artist and because of aspects of its artistic style.

In our replication, we had at least 294 participants per condition (after exclusions). Participants were randomized to one of five conditions. Four of the conditions were replications of the four conditions described above, and the fifth condition was included for the purposes of additional analyses. The fifth condition does not affect the replication of the study (as the participants randomized to the other four conditions are not affected by the additional fifth condition). In the fifth condition, participants read that the artwork was unique because it was created by a child prodigy using one-of-a-kind paints created specifically for the artwork that would not be created again.

All participants answered a series of questions about the artwork. They were asked to “indicate how well you think the following statements describe your feelings and beliefs about this piece of art:” (on a scale from “Strongly disagree (1)” to “Strongly agree (7)”). The questions captured participants’ views on the artwork’s sacredness, collective meaning, uniqueness, and usefulness, as well as participants’ positive or negative emotional response to the artwork. Sacredness in this context was defined as the perception that the artwork was “absolute and uncompromisable,” and unable to be “thought of in cost–benefit terms.” A complete list of the questions is in the “Study and Results in Detail” section.

Summary of the results

The original study tested 10 hypotheses (which we refer to here as Hypothesis 1 to Hypothesis 10, or H1 to H10 for short). They are listed in the table below, along with the original results and our replication results. (Please see the Study and Results in Detail section for an explanation of how the hypotheses were tested, as well as an explanation of the specific results.)

| Hypotheses | Original results | Our results | Replicated? |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Art with higher historical significance and collective spirituality will be rated as more collectively meaningful, compared to a control condition. | + (Positive finding) | + (Positive finding) | ✅ |

| H2: Art with higher historical significance will be rated as more collectively meaningful, compared to a control condition. | + | + | ✅ |

| H3: Art with higher collective spirituality will be rated as more collectively meaningful, compared to a control condition. | + | + | ✅ |

| H4: Art with higher historical significance and collective spirituality will be rated as more sacred, compared to a control condition. | + | + | ✅ |

| H5: Art with higher historical significance will be rated as more sacred, compared to a control condition. | + | + | ✅ |

| H6: Art with higher collective spirituality will be rated as more sacred, compared to a control condition. | + | + | ✅ |

| H7: H4 will be mediated by H1. | + | + | ✅ |

| H8: H5 will be mediated by H2. | + | + | ✅ |

| H9: H6 will be mediated by H3. | + | + | ✅ |

| H10: H4, H5, and H6 will not be mediated by other alternative mediators, including positivity, negativity, personal meaning, and utility of the painting. | – (Partially contradicted) | — (Mostly contradicted) | ❌ |

Study and Results in Detail

The questions included in the study are listed below. We used the same questions, including the same (in some cases unusual) punctuation and formatting, as the original study.

- Manipulation check questions:

- I believe, for many people this work of art evokes something profoundly spiritual.

- I believe, this work of art is a reflection of the past – a record of history.

- I believe, this piece of art is unique.

- Alternative mediator questions:

- Usefulness questions:

- This piece of art is useful for everyday use.

- You can use this piece of art in everyday life in a lot of different ways.

- This piece of art is functional for everyday use.

- I believe, this piece of art is unique.

- This piece of art makes me feel positive.

- This piece of art makes me feel negative.

- I personally find deep meaning in this piece of art that is related to my own life.

- Usefulness questions:

- Collective meaning questions:

- It represents something beyond the work itself – this work of art has deeper meaning to a vast number of people.

- A lot of people find deep meaning in this work of art– something more than what is shown in the painting.

- For many people this work of art represents something much more meaningful than the art itself.

- Sacredness questions:

- This piece of art is sacred.

- I revere this piece of art.

- This piece of art should not be compromised, no matter the benefits (money or otherwise).

- Although incredibly valuable, it would be inappropriate to put a price on this piece of art.

There were two order sequences:

- Participants answered questions about: (1) manipulation checks, (2) collective meaning, (3) alternative mediators, (4) sacredness

- Participants answered questions about: (1) manipulation checks, (2) sacredness, (3) alternative mediators, (4) collective meaning

Both our study and the original randomized each participant to one of the two order sequences above. In contrast to the original study, we also randomized the order of presentation of the questions within each set of questions.

In both the original study and in our replication, participants were excluded if any of the following conditions applied:

- They had missing data on any of the variables of interest

- They failed to report “the Lotus” (with or without a capital, and with or without “the”) when asked to provide the name of the artwork that they had been presented with

- They either failed to provide any information or provided random information that was irrelevant to details about the painting (as judged by two coders blinded to the study hypotheses, with the first author making the final decision in cases where the two coders disagreed). Please see the appendices for additional information about this.

- They report having seen or read about the artwork prior to completing the study (in response to the question, “Prior to this study, did you know anything about the artwork that you read about in this study? If so, what was your prior knowledge?”)

Testing Hypotheses 1-6

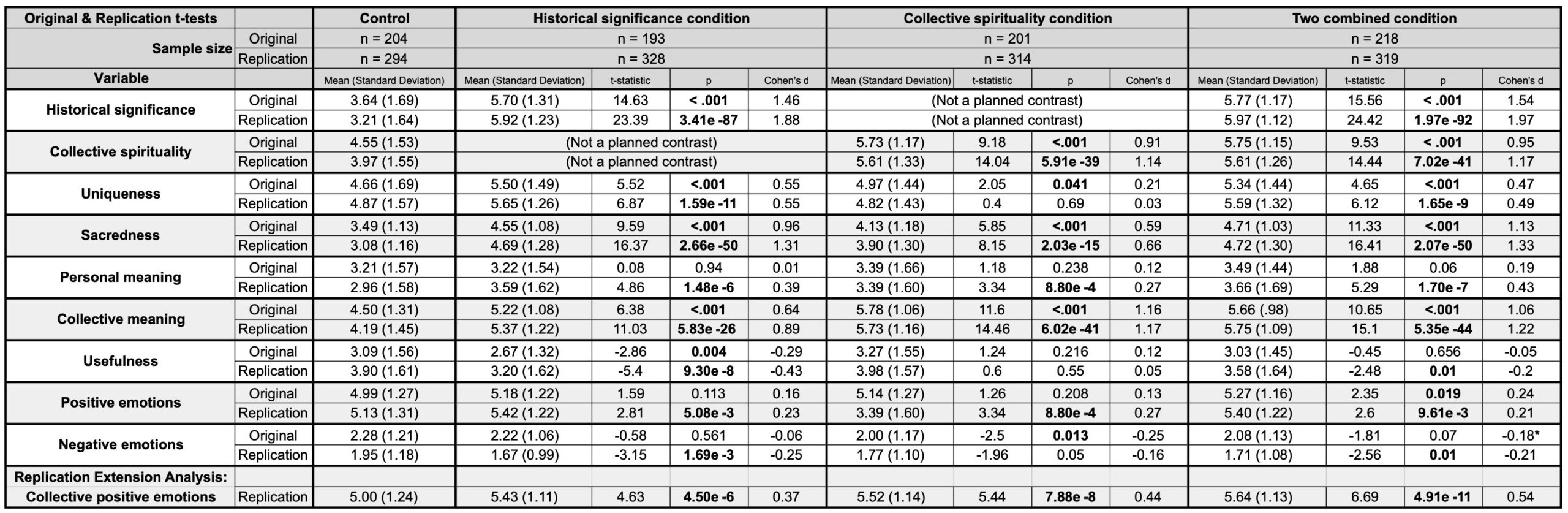

To test Hypotheses 1-6, both the original study and our replication used one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with experimental condition as the between-subjects factor and with each measured variable (in turn) as the dependent variable. This was followed up with independent samples t-tests comparing the collective meaning and sacredness of each treatment condition to the control condition. We performed our analyses for Hypotheses 1-6 in Jasp (Jasp Team, 2020; Jasp Team, 2023).

Tables showing all of the t-test results are available in the appendix. The t-test results for the collective meaning-related hypotheses (1-3), and the sacredness-related hypotheses (4-6) are shown below.

Results for Hypotheses 1-6

| Collective Meaning Hypotheses | Original results | Our results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H1: Art with higher historical significance and collective spirituality will be rated as more collectively meaningful, compared to a control condition. | Mcontrol (SD) = 4.50 (1.31) Mcombined (SD) = 5.66 (.98) t = 10.65 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 1.06 | Mcontrol (SD) = 4.19 (1.45) Mcombined (SD) = 5.75 (1.09) t = 15.1 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 1.22 | ✅ |

| H2: Art with higher historical significance will be rated as more collectively meaningful, compared to a control condition. | Mcontrol (SD) = 4.50 (1.31) Mhistorical (SD) = 5.22 (1.08) t = 6.38 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 0.64 | Mcontrol (SD) = 4.19 (1.45) Mhistorical (SD) = 5.37 (1.22) t = 11.03 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 0.89 | ✅ |

| H3: Art with higher collective spirituality will be rated as more collectively meaningful, compared to a control condition. | Mcontrol (SD) = 4.50 (1.31) Mspiritual (SD) = 5.78 (1.06) t = 11.6 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 1.16 | Mcontrol (SD) = 4.19 (1.45) Mspiritual (SD) = 5.73 (1.16) t = 14.46 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 1.17 | ✅ |

| Sacredness Hypotheses | Original results | Our results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| H4: Art with higher historical significance and collective spirituality will be rated as more sacred, compared to a control condition. | Mcontrol (SD) = 3.49 (1.13) Mcombined (SD) = 4.71 (1.03) t = 11.33 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 1.13 | Mcontrol (SD) = 3.08 (1.16) Mcombined (SD) = 4.72 (1.30) t = 16.41 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 1.33 | ✅ |

| H5: Art with higher historical significance will be rated as more sacred, compared to a control condition. | Mcontrol (SD) = 3.49 (1.13) Mhistorical (SD) = 4.55 (1.08) t = 9.59 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 0.96 | Mcontrol (SD) = 3.08 (1.16) Mhistorical (SD) = 4.69 (1.28) t = 16.37 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 1.31 | ✅ |

| H6: Art with higher collective spirituality will be rated as more sacred, compared to a control condition. | Mcontrol (SD) = 3.49 (1.13) Mspiritual (SD) = 4.13 (1.18) t = 5.85 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 0.59 | Mcontrol (SD) = 3.08 (1.16) Mspiritual (SD) = 3.90 (1.30) t = 8.15 p < 0.001 Cohen’s d = 0.66 | ✅ |

Conditional Process Analysis

Hypotheses 7-10 were assessed using a particular kind of mediation analysis known as multicategorical conditional process analysis, following Andrew Hayes’ PROCESS model. It is described in his book Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-based Approach. If you aren’t familiar with the terminology in this section, please check the Glossary of Terms.

The mediation analysis for Hypotheses 7-10 in the original study was conducted using model 4 of Andrew Hayes’ PROCESS macro in SPSS. We used the same model in the R version (R Core Team, 2022) of PROCESS. Model 4 includes an independent variable, an outcome or dependent variable, and a mediator variable, which are illustrated below in the case of this experiment.

In the model used in this study and illustrated above, there is:

- An independent variable (which can be categorical, as in this study),

- A dependent variable, and

- A mediator variable (that mediates the relationship between the independent and the dependent variable)

These variables are shown below, along with the names that are traditionally given to the different “paths” in the model.

In the diagram above…

- The “a” paths (from the independent variables to the mediator variable) are quantified by finding the coefficient of the independent variable in a linear regression predicting the mediator variable.

- The “b” and “c’ ” paths are quantified by finding the coefficients of the mediator and independent variables (respectively) in a regression involving the dependent variable as the outcome variable and all other relevant variables (in this case: the independent variable and the mediator variable) as the predictor variables.

In Hayes’ book, he states that mediation can be said to be occurring as long as the indirect effect – which is the multiple of the a and b coefficients – is different from zero. In other words, as long as the effect size of a*b (i.e, the path from the independent variable to the dependent variable via the mediator variable) is different from zero, the variable in the middle of the diagram above is said to be a significant mediator of the relationship between the independent and dependent variable. PROCESS uses bootstrapping (by default, with 10,000 resamples) to obtain an estimate of the lower and upper bound of the 95% confidence interval of the size of the ab path. If the confidence interval does not include 0, the indirect effect is said to be statistically significant.

The original random seed (used by the original authors in SPSS) was not saved. We corresponded with Andrew Hayes (the creator of PROCESS) about this and have included notes from that correspondence in the Appendices. In our replication, we used a set seed to allow other teams to reproduce and/or replicate our results in R.

Mediation results in more detail

Like the original paper, we found that collective meaning was a statistically significant mediator (with 95% confidence intervals excluding 0) of the relationship between each experimental condition and perceived sacredness.

In the table below, please note that “All conditions” refers to the mediation results when all experimental conditions were coded as “1”s and treated as the independent variable (with the control condition being coded as “0”).

| Mediator: Collective Meaning | Original Results | Replication Results | Replicated? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined vs. Control (H7) | [0.06, 0.15] | [0.6035, 0.9017] | ✅ |

| Historical vs. Control (H8) | [0.06, 0.16] | [0.4643, 0.7171] | ✅ |

| Spiritual vs. Control (H9) | [0.26, 0.54] | [0.5603, 0.8298] | ✅ |

| All Conditions | [0.05, 0.11] | [0.5456, 0.7699] | ✅ |

Mediation results for Hypothesis 10

For Hypothesis 10, the original study tested a variable as a potential mediator of the relationship between experimental condition and sacredness if there was a statistically significant difference in a particular variable across conditions when running the one-way ANOVAs. We followed the same procedure. See the notes on the mediation analysis plan in the appendices for more information about this.

When testing the alternative mediators of uniqueness and usefulness, the original study authors found that uniqueness was (and usefulness was not) a statistically significant mediator of the relationships between each of the experimental conditions and perceived sacredness. We replicated the results with respect to uniqueness, except in the case of the relationship between the spirituality condition and perceived sacredness, for which uniqueness was not a statistically significant mediator.

Insofar as we did not find that usefulness was a positive mediator of the relationship between experimental conditions and perceived sacredness, our results were consistent with the original study’s conceptual argument. However, unlike the original study authors, we found that usefulness was a statistically significant negative mediator (with an indirect effect significantly below zero) of the relationships between two of the experimental conditions (the historical condition and the combined condition) and perceived sacredness.

| Alternative Mediator: Uniqueness (H10) | Original Results | Replication Results | Replicated? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined vs. Control | [0.02, 0.06] | [0.1809, 0.3753] | ✅ |

| History vs. Control | [0.02, 0.10] | [0.1984, 0.3902] | ✅ |

| Spirituality vs. Control | [0.01, 0.13] | [-0.1082, 0.0705] | ❌ |

| All Conditions | [0.03, 0.07] | [0.1212, 0.2942] | ✅ |

| Alternative Mediator: Usefulness (H10) | Original Results | Replication Results | Replicated? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined vs. Control | [−.02, 0.01] | [-0.1216, -0.0128] | ❌ |

| History vs. Control | [−0.06, −0.01] | [-0.1689, -0.0549] | ✅ |

| Spirituality vs. Control | [−.02, 0.09] | [-0.0364, 0.0692] | ✅ |

| All Conditions | [−.02, 0.00] | [-0.0860, -0.0152] | ❌ |

In our replication, unlike in the original study, the one-way ANOVAs revealed statistically significant differences across conditions with respect to: personal meaning (F(3, 1251) = 11.35, p = 2.40 E-7), positive emotions (F(3, 1251) = 7.13, p = 4.35E-3), and negative emotions (F(3, 1251) = 3.78, p = 0.01).

As seen in the tables below, in each case, when we entered these alternative mediators, the variable was found to be a statistically significant mediator of the effect of all conditions (combined) on sacredness. Except for positive emotions, which wasn’t a statistically significant mediator of the effect of the spirituality condition (versus control) on sacredness, the listed variables were statistically significant mediators of the effects of all of the other experimental conditions (both combined and individually) on sacredness.

| Alternative Mediator: Personal Meaning (H10) | Original Results | Replication Results |

|---|---|---|

| Combined vs. Control | Not tested due to non-significant ANOVA results for these variables | [-0.1216, -0.0128] |

| History vs. Control | [0.1605, 0.3995] | |

| Spirituality vs. Control | [0.0787, 0.3144] | |

| All Conditions | [0.1684, 0.3619] |

| Alternative Mediator: Positive Emotions (H10) | Original Results | Replication Results |

|---|---|---|

| Combined vs. Control | Not tested due to non-significant ANOVA results for these variables | [0.0305, 0.2353] |

| History vs. Control | [0.0457, 0.2555] | |

| Spirituality vs. Control | [-0.0914, 0.1265] | |

| All Conditions | [0.0144, 0.2003] |

| Alternative Mediator: Negative Emotions (H10) | Original Results | Replication Results |

|---|---|---|

| Combined vs. Control | Not tested due to non-significant ANOVA results for these variables | [0.0080, 0.0900] |

| History vs. Control | [0.0208, 0.1118] | |

| Spirituality vs. Control | [0.0000, 0.0762] | |

| All Conditions | [0.0186, 0.1019] |

There were 24 Buddhists in the sample. As in the original study, analyses were performed both with and without Buddhists in the sample, and the results without Buddhists were consistent with the results with them included. All findings that were statistically significant with the Buddhist included were also statistically significant (and with effects in the same direction) as the dataset with the Buddhists excluded, except for the fact that, when Buddhists were included in the sample (as in the tables above), usefulness did not mediate the relationship between the spiritual significance condition (versus control) and sacredness (95% confidence interval: [-0.0364, 0.0692]), whereas with the Buddhist-free dataset, usefulness was a statistically significant (and negative) mediator of that relationship (95% confidence interval: [-0.1732, -0.0546]).

Interpreting the results

Most of the findings in the original study were replicated in our study. However, our results diverged from the original paper’s results when it came to several of the subcomponents of Hypothesis 10. Some of the alternative mediators included in the original study questions weren’t entered into mediation analyses in the original paper because the ANOVAs had not demonstrated statistically significant differences in those variables across conditions. However, we found significant differences for all of these variables in the ANOVAs that we ran on the replication dataset, so we tested them in the mediation analyses.

In the original study, uniqueness was a significant mediator of the relationship between experimental condition and perceived sacredness, which partially contradicted Hypothesis 10. In our replication study, not only was uniqueness a significant mediator of this relationship, but so was personal meaning, negative emotions, and (except for the relationship between spiritual significance and sacredness) so were usefulness and positive emotions. Thus, our study contradicted most of the sub-hypotheses in Hypothesis 10.

Despite the fact that multiple alternative mediators were found to be significant in this study, when these alternative mediators were included as covariates, collective meaning continued to be a significant mediator of the relationship between experimental condition and perceived sacredness. This means that even when alternative mediators are considered, the main finding (that collective meaning influences sacredness judgments) holds in both the original study and our replication.

We had concerns about the interpretation of the study results that are reflected only in the Clarity Rating. These revolve around (1) the manipulation of uniqueness and the way in which this was reported in the study and (2) the degree to which alternative explanations can be ruled out by the study’s design and the results table.

Manipulating Uniqueness

The control condition in the original study did not manipulate uniqueness in the way it was intended to manipulate it.

In the original study, the control condition was introduced for the following reason:

“By manipulating how historic the artwork was [in our previous study], we may have inadvertently affected perceptions of how unique the artwork was, since old things are typically rare, and there may be an inherent link between scarcity and sacredness…to help ensure that collective transcendence beliefs, and not these alternative mechanisms, are driving our effects, in Study 4 we employed a more stringent control condition that …emphasized the uniqueness of the art without highlighting its historical significance or its importance to collective spirituality”

In other words, the original authors intended for uniqueness to be ruled out as an explanation for higher ratings of sacredness observed in the experimental conditions. Throughout their pre-registration, the authors referred to “a control condition manipulating the art’s uniqueness” as their point of comparison for both collective meaning and sacredness judgments of artwork across the different experimental conditions.

Unfortunately, however, their control condition did not successfully induce perceptions of uniqueness in the way that the authors intended. The control condition was significantly less unique than each of the experimental conditions, whereas to serve the purpose it had been designed for, it should have been perceived to be at least as unique as the experimental conditions.

Although the paper did mention this finding, it did not label it as a failed manipulation check for the control condition. We think this is one important area in which the paper could have been written more clearly. When introducing study 4, they emphasized the intention to rule out uniqueness as an explanation for the different sacredness ratings. In the discussion paragraph associated with study 4, they again talk about their findings as if they have ruled out the uniqueness of the artwork as an explanation. However, as explained above, the uniqueness of the artwork was not ruled out by the study design (nor by the study findings).

For clarity in this report and our pre-registration, we refer to the fourth condition as simply “a control condition.” In addition, in an attempt to address these concerns regarding the interpretation of the study’s findings, we included a fifth condition that sought to manipulate the uniqueness of the artwork in such a way that the perceived uniqueness of the artwork in that condition was at least as high on the Likert scale as the uniqueness of the artwork in the experimental conditions. Please note that this fifth condition was only considered in our assessment of the Clarity rating for the current paper, not the Replicability rating. Please see the appendix for the results related to this additional condition.

The paper’s discussion of alternative mediators

The claim that “Study 4’s design also helped rule out a number of alternative explanations” is easily misinterpreted.

In the discussion following study 4, the original authors claim that:

“Study 4’s design also helped rule out a number of alternative explanations, including the uniqueness of the artwork, positivity and negativity felt toward the art, and the personal meaning of the work.”

The fact that this explanation includes the world “helped” is key – if the claim had been that the study design “definitively ruled out” alternative explanations, it would have been false. This is because, in the absence of support for the alternative mediators that were tested, the most one could say is that the experiment failed to support those explanations, but due to the nature of null hypothesis significance testing (NHST), those alternative explanations cannot be definitively “ruled out.” In order to estimate the probability of the null hypothesis directly, the paper would have needed to use Bayesian methods rather than only relying on frequentist methods.

Especially in the context of NHST, it is not surprising that Hypothesis 10 was far less supported (i.e., more extensively contradicted) by our results than by the results of the original study, because of our larger sample size. The claim quoted above could be misinterpreted if readers under-emphasized the word “helped” or readers they focused on the idea of “ruling out” the mediators with null results.

Another way in which this part of the discussion of study 4 in the paper is less than optimally clear is in the discrepancy between the discussion and the mediation results table. Rather than showing the uniqueness of the artwork was not a likely explanation, the original paper only showed that it was not the only explanation. The authors recorded these findings in a table (Table 9 in the original paper), but the discussion did not discuss the implications of the finding in the table that uniqueness was also a significant mediator of the relationship between spiritual, historical, and combined historical and spiritual significance on the perceived sacredness of artwork.

Interestingly, however, when we ran a mediation analysis on the original paper’s data, and entered uniqueness as a mediator, with collective meaning and usefulness as covariates, we found that uniqueness was, indeed, not a statistically significant mediator (using the same random seed as throughout this write-up, the 95% confidence interval included 0: [-0.0129, 0.0915]). This aligns with the claim in the discussion that the original study had not found evidence in favor of it being a mediator. However, such results do not appear to be included in the paper; instead, Table 9 in the original paper shows mediation results for each individual mediator variable on their own (without the other variables entered as covariates), and in that table, uniqueness is a significant mediator (which is contrary to what the discussion section implies).

Our study also replicated the finding that uniqueness was a significant mediator between experimental condition and perceived sacredness (when entered into the model without any covariates), except in the case of the spiritual condition versus control. Additionally, in our study, we found several more mediators that were statistically significant by the same standards of statistical significance used by the original authors (again, when entered into the model without any covariates).

The overall claim that collective meaning remains a mediator above and beyond the other mediators considered in the study remained true when the other variables that appeared relevant (uniqueness and usefulness) were entered as covariates in the original study data. The claim was also true for our dataset, including when all the considered mediators were entered as covariates.

Conclusion

We replicated 90% of the results reported in study 4 from the paper, “Collective transcendence beliefs shape the sacredness of objects: the case of art.” The original study’s methods and data were mostly recorded and shared transparently, but the exclusion procedures were only partially shared and the related free-text data were not shared; there were also some minor deviations from the pre-registration. The original paper would have benefited from clearer explanations of the study’s results and implications. In particular, we suggest that it would have been preferable if the discussion section for study 4 in the original paper had acknowledged that the experiment had not controlled for uniqueness in the way that had been originally planned, and if the table of results and discussion had been consistent with each other.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the team who ran the original study for generously reviewing our materials, sending us their original study materials, helping us to make this replication a faithful one, and providing helpful, timely feedback on our report. (As with all our reports, though, the responsibility for the contents of the report remains with the author and the rest of the Transparent Replications team.)

Many thanks to Amanda Metskas for her extensive involvement throughout the planning, running, and reporting of this replication study. Amanda had a central role in the observations we made about the original study’s control condition, and she also highlighted the subsequent necessity of including an alternative control condition in our study. Many thanks also go to Spencer Greenberg for his helpful feedback throughout, to our hypothesis-blinded coders, Alexandria Riley and Mike Riggs, for their help in excluding participants according to our exclusion protocol, and to our Ethics Evaluator. Thank you to the forecasters on Metaculus who engaged with our study description and made predictions about it. Last but certainly not least, many thanks to our participants for their time and attention.

Purpose of Transparent Replications by Clearer Thinking

Transparent Replications conducts replications and evaluates the transparency of randomly-selected, recently-published psychology papers in prestigious journals, with the overall aim of rewarding best practices and shifting incentives in social science toward more replicable research.

We welcome reader feedback on this report, and input on this project overall.

Appendices

Additional information about the pre-registration

In cases of discrepancies between a paper and a pre-registration, we take note of the differences, as this is relevant to the transparency of the paper, but we replicate what the authors described actually doing in the paper.

There were differences between the pre-registered analysis plan and what was actually done (explained in the next section). In addition to this, there were subtle wording and formatting differences between the text in the pre-registration and the text used in the conditions in the actual study. Having said this, none of the wording discrepancies altered the meaning of the conditions.

The pdf of the study questions that the team shared with us also included bold or underlined text in some questions, and these formatting settings were not mentioned in the pre-registration. However, we realize that bold or underlined text entered into the text fields of an OSF pre-registration template do not display as bold or underlined text when the pre-registration is saved.

Additional information about the exclusion criteria

In preparation for replicating the process undertaken to implement exclusion criterion #3, we requested a copy of the written instructions given to the hypothesis-blinded coders in the original study. The original authorship team responded with the following:

“I had a meeting/training session with my coders before letting them code everything. Like ask them to code 10% to see if they have high agreement, if not we discuss how to reach agreement. For example the response has to contain at least two critical informations about the artwork etc. so the instructions may vary depending on participants’ responses.”

We wanted our exclusion procedures to be as replicable as possible, so instead of providing a training session, we provided a written guidelines document for our coders. See here for the guidelines document we provided to our coders. There was moderate agreement between the two hypothesis-blinded coders (ICC1 = 0.58, ICC2 = 0.59) and all disagreements were resolved by the first author.

Notes on corresponding with the original authors

There were some cases where the original authorship team’s advice was not consistent with what they had recorded in their pre-registration and/or paper (which we attributed to the fact that the study was conducted some time ago). In those cases, we adhered to the methods in the pre-registration and paper.

Full t-test results

Notes on Andrew Hayes’ PROCESS models

The original authorship team had used the PROCESS macro in SPSS and did not record a random seed. So the current author emailed Andrew Hayes about our replication and asked whether there is a default random seed that is used in SPSS, so that we could specify the same random seed in R. His response was as follows:

If the seed option is not used in the SPSS version, there is no way of recovering the seed for the random number generator. Internally, SPSS seeds it with a random number (probably based on the value of the internal clock) if the user doesn’t specify as seed.

SPSS and R use different random number generators so the same seed will produce different bootstrap samples. Since the user can change the random number generator, and the default random number generator varies across time, there really is no way of knowing for certain whether using the same seed will reproduce results.

Likewise, if you sort the data file rows differently than when the original analysis was conducted, the same seed will not reproduce the results because the resampling is performed at the level of the rows. This is true for all versions.

Notes on mediation analysis plans in the pre-registration

In their pre-registration, the authors had said: “We will also conduct this same series of mediation analyses for each of the alternative mediators described above. If any of the alternative mediators turn out to be significant, we will include these significant alternative mediators in a series of simultaneous mediation analyses (following the same steps as described above) entering them along with collective meaning.” In contrast, in their paper, they only reported on mediation analyses for the variables for which there were significant ANOVA results. And when they found a significant medicator, in the paper they described rerunning ANOVAs while controlling for those mediators, whereas in the pre-registration they had described rerunning mediation analyses with the additional variables as covariates.

Notes on the mediators considered in the original study design

In their set of considered explanations for the perceived sacredness of art, the authors considered the effects of (i) individual meaningfulness in addition to (ii) collective meaning, and they considered the effects of (i) individual positive emotions, but they did not consider the effects of (ii) collective positive emotions.

The original study authors included a question addressing the individual meaningfulness of the artwork, as they acknowledged that the finding about collective meaning was more noteworthy if it existed above and beyond the effects of individual meaningfulness. They also included a question addressing individual positive emotions so that they could examine the impact of this variable on sacredness. In the context of this study, it seems like another relevant question to include would relate to the effects of collective positive emotions (as the collective counterpart to the question about individual positive emotions). One might argue that this is somewhat relevant to the clarity of this paper: ideally, the authors would have explained the concepts in such a way as to make the inclusion of a question about collective positive emotions an obvious consideration.

We therefore included a question addressing collective positive emotions. (We did not include multiple questions, despite the fact that there were multiple questions addressing collective meaningfulness, because we wanted to minimize the degree to which we increased the length of the study.) The additional question was included as the very last question in our study, so that it had no impact on the assessment of the replicability of the original study (as the replication component was complete by the time participants reached the additional question).

Results from extensions to the study

The t-test results table above includes a row of results (pertaining to the effect of collective positive emotions) that were outside the scope of the replication component of this project.

We also conducted an extra uniqueness versus control comparison which is somewhat relevant to the clarity rating of the study, but represents an extension to the study rather than a part of the replicability assessment.

Our newly-introduced, fifth condition was designed to be perceived as unique. It was rated as more unique than the original study’s control condition, and this difference was statistically significant (Mnew_condition = 5.26; Mcontrol = 4.87; student’s t-test: t(611) = 1.26 E-3; d = -0.26). It was also rated as more unique than the spiritual significance condition; however, it was rated as less unique than the individual historical significance condition and the combined historical and spiritual significance condition.

In addition to being rated as more unique than the original control, the fifth condition was also rated as more historically significant than the control condition, and this difference was also statistically significant. Having said this, the degree of perceived historical significance was still statistically significantly lower than the perceived historical significance in each of the (other) experimental conditions (Mnew_condition = 3.52; Mcontrol = 3.21; student’s t-test: t(611) = 0.02; d = -0.19).

In summary, our results suggest that our fifth condition provides a more effective manipulation of the level of uniqueness of the artwork (in terms of its effect on uniqueness ratings) compared to the original control. However, the historically significant conditions were both still rated as more unique than the fifth condition. This means that the study design has been unable to eliminate differences in perceived uniqueness between the control and experimental conditions. Since more than one variable is varying across the conditions in the study, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions from this study. It would be premature to say that uniqueness is not contributing to the differences in perceived sacredness observed between conditions.

So, once again, like the original authors, we did not have a condition in the experiment that completely isolated the effects of collective meaning because our control condition did not serve its purpose (it was meant to have the same level of uniqueness as the experimental conditions while lacking in historical and spiritual significance, but instead it had a lower level of perceived uniqueness than two of the other conditions, and it was rated as more historically significant than the original control).

If future studies sought to isolate the effects of collective meaning as distinct from uniqueness, teams might want to give consideration to instead trying to reduce the uniqueness of an already spiritually meaningful or historically significant artwork, by having some conditions in which the artwork was described as one of many copies (for example), so that comparisons could be made across conditions that have different levels of uniqueness but identical levels of historical and spiritual meaningfulness. This might be preferable to trying to create a scenario with a unique artwork that lacks at least historical significance (potentially as a direct consequence of its uniqueness).

The table below provides t-test results pertaining to our replication dataset, comparing the control condition with the alternative control condition that we developed.

| Replication Analysis Extension | Control n = 294 | Alternative control n = 319 | |||

| Variable | Mean (Stnd Dev.) | Mean (Stnd Dev.) | t value | p | Cohen’s d |

| Historical significance | 3.21 (1.64) | 3.52 (1.55) | 2.4 | 0.02 | 0.19 |

| Collective spirituality | 3.97 (1.55) | 4.16 (1.48) | 1.56 | 0.12 | 0.13 |

| Uniqueness | 4.87 (1.57) | 5.26 (1.38) | 3.24 | 1.26e -3 | 0.26 |

| Sacredness | 3.08 (1.16) | 3.36 (1.30) | 2.79 | 5.49e -3 | 0.23 |

| Personal meaning | 2.96 (1.58) | 3.03 (1.51) | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.04 |

| Collective meaning | 4.19 (1.45) | 4.50 (1.37) | 2.75 | 6.20e -3 | 0.22 |

| Usefulness | 3.90 (1.61) | 3.50 (1.61) | -3.09 | 2.08e -3 | -0.25 |

| Positive emotions | 5.13 (1.31) | 5.09 (1.18) | -0.41 | 0.68 | -0.03 |

| Collective positive emotions | 5.00 (1.24) | 4.99 (1.07) | 0.1 | 0.92 | 7.91e -3 |

| Negative emotions | 1.95 (1.18) | 1.92 (1.14) | 0.26 | 0.8 | 0.02 |

In addition to investigating an alternative control condition, we included one additional potential mediator: collective positive emotions. The reasoning for this was explained above. Our results suggest that perceived collective positive emotions could also mediate the relationship between experimental conditions and the perceived sacredness of artwork. It may be difficult to disentangle the effects of collective meaning and collective positive emotions, since both of these varied significantly across experimental conditions and since there was a moderate positive correlation between them (Pearson’s r = 0.59).

The additional variable that we collected, perceived collective positive emotions, was a statistically significant mediator of the relationship between all of the experimental conditions and perceived sacredness.

| Alternative Mediator: Collective Positive Emotions (extension to H10) | Results |

|---|---|

| Combined vs. Control | [0.2172, 0.4374] |

| History vs. Control | [0.1402, 0.3476] |

| Spirituality vs. Control | [0.1765, 0.3795] |

| All Conditions | [0.2068, 0.3897] |

Glossary of terms

Please skip this section if you are already familiar with the terms. If this is the first time you are reading about any of these concepts, please note that the definitions given are (sometimes over-)simplifications.

- Independent variable (a.k.a. predictor variable): a variable in an experiment or study that is altered or measured, and which affects other (dependent) variables. [In many studies, including this one, we don’t know whether an independent variable is actually influencing the dependent variables, so calling it a “predictor” variable may not be warranted, but many models implicitly assume that this is the case. The term “predictor” variable is used here because it may be more familiar to readers.]

- Dependent variable (a.k.a. outcome variable): a variable that is influenced by an independent variable. [In many studies, including this one, we don’t know whether a dependent variable is actually being causally influenced by the independent variables, but many models implicitly assume that this is the case.]

- Null Hypothesis: in studies investigating the possibility of a relationship between given pairs/sets of variables, the Null Hypothesis assumes that there is no relationship between those variables.

- P-values: the p-value of a result quantifies the probability that a result at least as extreme as that result would have been observed if the Null Hypothesis were true. All p-values fall in the range (0, 1].

- Statistical significance: by convention, a result is deemed to be statistically significant if the p-value is below 0.05, meaning that there is a 5% chance that a result at least as extreme as that result would have occurred if the Null Hypothesis were true.

- The more statistical tests conducted in a particular study, the more likely it is that some results will be statistically significant due to chance. So, when multiple statistical tests are performed in the same study, many argue that one should correct for multiple comparisons.

- Statistical significance also does not necessarily translate into real-world/clinical/practical significance – to evaluate that, you need to know about the effect size as well.

- Linear regression: this is a process for predicting levels of a dependent/outcome variable (often called a y variable) based on different levels of an independent/predictor variable (often called an x variable), using an equation of the form y = mx + c (where m is the rate at which the dependent/outcome variable changes as a function of changes in the independent/predictor variable, and c describes the level of the dependent variable that would be expected if the independent/predictor variable, x, was set to a level of 0).

- Mediator variable: a variable which (at least partly) explains the relationship between a predictor variable and an outcome variable. [Definitions of moderation vary, but Andrew Hayes defines it as occurring any time when an indirect effect – i.e., the effect of a predictor variable on the outcome variable via the mediator variable, is statistically significantly different from zero.]

- Moderator variable: a variable which changes the strength or direction of a relationship between a predictor variable and an outcome variable.

- Categorical variables: these are variables described in terms of categories (as opposed to being described in terms of a continuous scale).

References

Chen, S., Ruttan, R. L., & Feinberg, M. (2022). Collective transcendence beliefs shape the sacredness of objects: The case of art. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 124(3), 521–543. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000319

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149-1160. Download PDF

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis a regression-based approach (Third edition). The Guilford Press.

JASP Team (2020). JASP (Version 0.14.1 ) [Computer software].

JASP Team (2023). JASP (Version 0.17.3) [Computer software].

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for

Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/.