Executive Summary

We ran replications of studies three (3) and four (4) from this paper. These studies found that:

- People have less support for behavioral nudges (such as sending reminders about appointment times) to prevent failures to appear in court than to address other kinds of missed appointments

- People view missing court as more likely to be intentional, and less likely to be due to forgetting, compared to other kinds of missed appointments

- The belief that skipping court is intentional drives people to support behavioral nudges less than if they believed it was unintentional

We successfully replicated the results of studies 3 and 4. Transparency was strong due to study materials and data being publicly available, but neither study being pre-registered was a weakness. Overall the studies were clear in their analysis choices and explanations, but clarity could have benefited from more discussion of alternative explanations and the potential for results to change over time.

Full Report

Study Diagrams

Study 3 Diagram

Study 4 Diagram

Replication Conducted

We ran a replication of studies 3 and 4 from: Fishbane, A., Ouss, A., & Shah, A. K. (2020). Behavioral nudges reduce failure to appear for court Science, 370(6517), eabb6591.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb6591

How to cite this replication report: Transparent Replications, & Blake, V. (2023). Report #4: Replication of two studies from “Behavioral nudges reduce failure to appear for court” (Science | Fishbane et al. 2020). Clearer Thinking. https://replications.clearerthinking.org/replication-2020Science370-6517

(Report DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17716155)

Key Links

- Go to the Research Box for this report to view our pre-registrations, experimental materials, de-identified data, and analysis files.

- See the predictions made about this study:

- See the Manifold Markets prediction markets for this study:

- For study 3 – 7.8% probability given to both claims replicating (corrected to exclude market subsidy percentage)

- For study 4 – 21.4% probability given to all 3 claims replicating (corrected to exclude market subsidy percentage)

- See the Metaculus prediction pages for this study

- For study 3 – Community prediction was 49% “yes” for both claims replicating (note: some forecasters selected “yes” for more than one possible outcome)

- For study 4 – Community prediction was 35% “yes” for all three claims replicating (note: some forecasters selected “yes” for more than one possible outcome)

- See the Manifold Markets prediction markets for this study:

- Download a PDF of the original paper

- View supporting materials for the original study on OSF

Overall Ratings

Our Replicability and Clarity Ratings are single-criterion ratings. Our Transparency Ratings are derived from averaging four sub-criteria (and you can see the breakdown of these in the second table).

| Transparency: how transparent was the original study? | |

| Replicability: to what extent were we able to replicate the findings of the original study? | All five findings from the original studies replicated (100%). |

| Clarity: how unlikely is it that the study will be misinterpreted? | Results were communicated clearly. Some alternative interpretations of the results could have been provided and the potential for the results to change over time could have been addressed. |

Detailed Transparency Ratings

For an explanation of how the ratings work, see here.

| Overall Transparency Rating: | |

|---|---|

| 1. Methods Transparency: | The materials were publicly available and almost complete, and remaining materials were provided on request. |

| 2. Analysis Transparency: | The analyses for both studies 3 and 4 were commonly-completed analyses that were described in enough detail for us to be able to reproduce the same results on the original dataset. |

| 3. Data availability: | The data were publicly available and complete. |

| 4. Pre-registration: | Neither study 3 nor study 4 was pre-registered. |

Summary of Study and Results

We replicated the results from laboratory experiments 3 and 4 from the original paper. The original paper conducted 5 laboratory experiments in addition to a field study, but we chose to focus on studies 3 and 4.

We judged study 3 to be directly relevant to the main conclusions of the paper and chose to focus on that first. Following communication with the original authorship team, who were concerned that study 3’s results may be affected by potential changes in public attitudes to the judicial system over time, we decided to expand our focus to include another study whose findings would be less impacted by changes in public attitudes (if those had occurred). We selected study 4 as it included an experimental manipulation. When considering one of the significant differences observed in study 4 between two of its experimental conditions (between the “mistake” and “control” conditions, explained below), we thought that this difference would only cease to be significant if the hypothetical changes in public opinion (since the time of the original study) had been very dramatic.

Our replication study of study 3 (N = 394) and study 4 (N=657) examined:

- Whether participants have lower support for using behavioral nudges to reduce failures to appear in court than for using behavioral nudges to reduce failures to complete other actions (study 3),

- Whether participants rate failures to attend court as being less likely to be due to forgetting and more likely to be intentional, compared to failures to attend non-court appointments (study 3), and

- The different proportions of participants selecting behavioral nudges three across different experimental conditions (study 4).

The next sections provide a more detailed summary, methods, results, and interpretation for each study separately.

Study 3 summary

In the original study, participants were less likely to support using behavioral nudges (as opposed to harsher penalties) to reduce failures to appear in court than to reduce failures to attend other kinds of appointments. They also rated failures to attend court as being less likely to be due to forgetting and more likely to be intentional, compared to failures to attend non-court appointments.

Study 3 methods

In the original study and in our replication, participants read five scenarios (presented in a randomized order) about people failing to take a required action: failing to appear for court, failing to pay an overdue bill, failing to show up for a doctor’s appointment, failing to turn in paperwork for an educational program, and failing to complete a vehicle emissions test.

For each scenario, participants rated the likelihood that the person missed their appointment because they did not pay enough attention to the scheduled date or because they simply forgot. Participants also rated how likely it was that the person deliberately and intentionally decided to skip their appointment.

Finally, participants were asked what they thought should be done to ensure that other people attend their appointments. They had to choose one of three options (shown in the following order in the original study, but shown in randomized order in our study):

- (1) Increase the penalty for failing to show up

- (2) Send reminders to people about their appointments, or

- (3) Make sure that appointment dates are easy to notice on any paperwork

The original study included 301 participants recruited from MTurk. Our replication included 394 participants (which meant we had 90% power to detect an effect size as low as 75% of the original effect size) recruited from MTurk via Positly.

Study 3 results

| Hypothesis | Original result | Our result | Replicated? |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants have lower support for using behavioral nudges to reduce failures to appear for court (described in a hypothetical scenario) than for using behavioral nudges to reduce failures to attend other kinds of appointments (described in four other scenarios). | + | + | ✅ |

| Participants rate failures to attend court as being: (1) less likely to be due to forgetting and (2) more likely to be intentional, compared to failures to attend non-court appointments (captured in four different scenarios). | + | + | ✅ |

In the original study, participants were less likely to support behavioral nudges to reduce failures to appear in court compared to failures to attend other appointments (depicted in four different scenarios) (Mcourt = 43%, SD = 50; Mother actions = 65%, SD = 34; paired t test, t(300) = 8.13, p < 0.001). Compared to failures to attend other kinds of appointments, participants rated failures to attend court as being less likely to be due to forgetting (Mcourt = 3.86, SD = 2.06; Mother actions = 4.24, SD = 1.45; paired t test, t(300) = 3.79, p < 0.001) and more likely to be intentional (Mcourt = 5.17, SD = 1.75; Mother actions = 4.82, SD = 1.29; paired t test, t(300) = 3.92, p < 0.001).

We found that these results replicated. There was a significantly lower level of support for behavioral nudges to reduce failures to appear for court (Mcourt = 42%, SD = 50) compared to using behavioral nudges to reduce failures to complete other actions (Mother actions = 72%, SD = 32; paired t test, t(393) = 12.776, p = 1.669E-31).

Participants rated failures to attend court as being less likely to be due to forgetting (Mcourt = 3.234, SD = 1.848) compared to failures to attend non-court appointments (Mother actions = 3.743, SD = 1.433); and this difference was statistically significant: t(393) = 7.057, p = 7.63E-12.

Consistent with this, participants also rated failures to attend court as being more likely to be intentional (Mcourt = 4.972, SD = 1.804) compared to failures to attend non-court appointments conditions (Mother actions = 4.492, SD = 1.408); and this difference was statistically significant: t(393) = 6.295, p = 8.246E-10.

A table with these complete results is available in the appendices.

Interpreting the results of study 3

The authors make the case that people generally ascribe “greater intentionality to failures to appear.” They also argue that it is these beliefs that contribute to the stance that harsher penalties are more effective than behavioral nudges for reducing failures to appear.

We generally are inclined to believe that the results are representative of their interpretation. However, there was still room for the original authors to be clearer about the interpretation of their results, particularly with respect to the degree to which they thought their results might change over time.

When our team first reached out to the original authors about replicating study 3 from their paper, they were concerned that the results may have changed over time due to documented changes in the public’s attitudes toward the judicial system since the time the studies were completed. On reflection, we agreed that it was an open question as to whether the results in study 3 would change over time due to changing public opinion towards the criminal justice system in response to major events like the murder of George Floyd. Unfortunately, however, the authors’ belief that the results were sensitive to (potentially changing) public opinions rather than representing more stable patterns of beliefs, was not mentioned in the original paper.

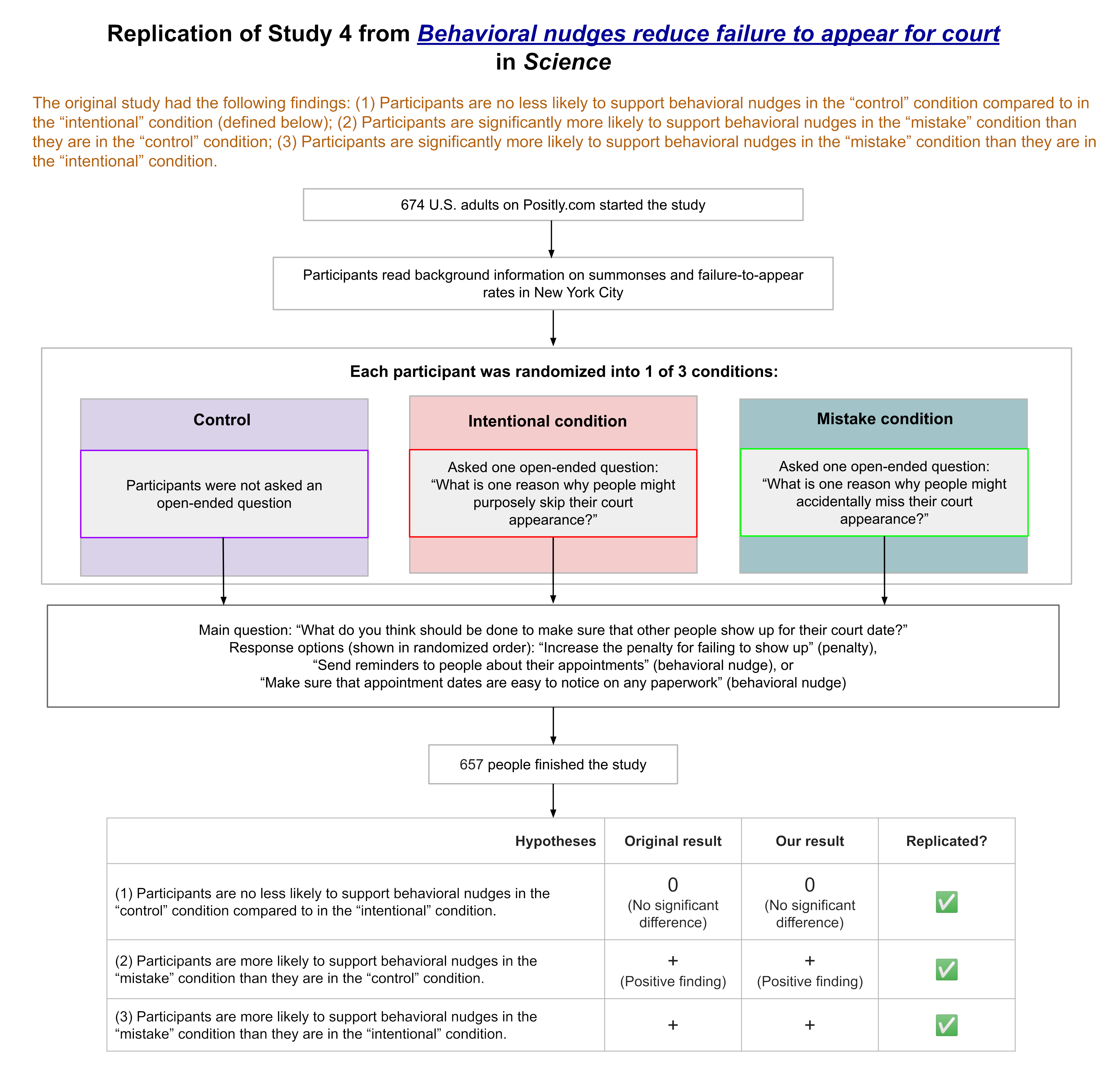

Study 4 summary

In the original study, participants read a scenario about failures to appear in court, then they were randomized into one of three groups – an “intentional” condition, where participants were asked to write one reason why someone would intentionally skip court, a “mistake condition,” where they were asked to write a reason someone would miss it unintentionally, and a “control” condition, which asked neither of those questions. All participants were then asked what should be done to reduce failures to appear. Participants in the “intentional” and “control” conditions chose to increase penalties with similar frequencies, while participants in the “mistake” condition were significantly more likely to instead support behavioral nudges (as opposed to imposing harsher penalties for failing to appear) compared to people in either of the other conditions.

Study 4 methods

In the original study and in our replication, all participants read background information on summonses and failure-to-appear rates in New York City. This was followed by a short experiment (described below), and at the end, all participants selected which of the following they think should be done to reduce the failure-to-appear rate: (1) increase the penalty for failing to show up, (2) send reminders to people about their court dates, (3) or make sure that court dates are easy to notice on the summonses. (These were shown in the order listed in the original study, but we showed them in randomized order in our replication.)

Prior to being asked the main question of the study (the “policy choice” question), participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions.

- In the control condition, participants made their policy choice immediately after reading the background information.

- In the intentional condition, after reading the background information, participants were asked to type out one reason why someone might purposely skip their court appearance, and then they made their policy choice.

- In the mistake condition, participants were asked to type out one reason why someone might accidentally miss their court appearance, and then they made their policy choice.

The original study included 304 participants recruited from MTurk. Our replication included 657 participants (which meant we had 90% power to detect an effect size as low as 75% of the original effect size) recruited from MTurk via Positly.

Study 4 results

| Hypotheses | Original results | Our results | Replicated? |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Participants are no less likely to support behavioral nudges in the “control” condition compared to in the “intentional” condition. | 0 | 0 | ✅ |

| (2) Participants are more likely to support behavioral nudges in the “mistake” condition than they are in the “control” condition. | + | + | ✅ |

| (3) Participants are more likely to support behavioral nudges in the “mistake” condition than they are in the “intentional” condition. | + | + | ✅ |

In the original study, there was no statistically significant difference between the proportion of participants selecting behavioral nudges in the control versus the intentional condition (control: 63% supported nudges; intentional: 61% supported nudges; χ2(1, N = 304) = 0.09; p = 0.76).

On the other hand, 82% of participants selected behavioral nudges in the mistake condition (which was a significantly larger proportion than both the control condition [χ2(1, N = 304) = 9.08; p = 0.003] and the intentional condition [χ2(1, N = 304) = 10.53; p = 0.001]).

In our replication, we assessed whether, similar to the original study, (1) participants in the “control” condition and the “intentional” condition do not significantly differ in their support for behavioral nudges; (2) Participants are more likely to support behavioral nudges in the “mistake” condition than they are in the “control” condition; and (3) Participants are more likely to support behavioral nudges in the “mistake” condition than they are in the “intentional” condition. We found that these results replicated:

(1) χ2 (1, N = 440) = 1.090, p = 0.296. Participants’ support for behavioral nudges in the control condition (where 64.3% selected behavioral nudges) was not statistically significantly different from their support for behavioral nudges in the intentional condition (where 69.0% selected behavioral nudges).

(2) χ2 (1, N = 441) = 34.001, p = 5.509E-9. Participants were more likely to support behavioral nudges in the mistake condition (where 88.0% selected behavioral nudges) than in the control condition (where 64.3% selected behavioral nudges).

(3) χ2 (1, N = 433) = 23.261, p = 1.414E-6. Participants were more likely to support behavioral nudges in the mistake condition (where 88.0% selected behavioral nudges) than in the intentional condition (where 69.0% selected behavioral nudges).

A table with these complete results is available in the appendices.

Interpreting the results of study 4

The original authors make the case that participants are more supportive of behavioral nudges instead of stiffer punishments when they think that people missed their appointments by mistake. The original authors noted that support for nudges to reduce failures to appear for court in Study 4 (in the control arm, 63% supported behavioral nudges) was higher than in Study 3 (where 43% supported behavioral nudges to reduce failures to appear for court). In the control arm of our replication of Study 4, we also found a higher support for nudges to reduce failures to appear (64% supported behavioral nudges) compared to in our replication of Study 3 (where 42% supported behavioral nudges to reduce failures to appear for court). The original authors attribute the difference to the background information (e.g., the baseline failure-to-appear rate) that was provided to participants in Study 4. Our results are consistent with their interpretation.

We saw that participants assigned to the control and intentional conditions behaved similarly. The results seem to be consistent with the original study authors’ hypothesis that people default to thinking that failures to appear for court are intentional. In the original study, there had been a possible alternative interpretation: the control and intentional conditions could have both had similar responses because the top answer option on display was to increase penalties – in the original paper, the authors argued that the fact that participants in the control condition behaved similarly to the intentional condition was evidence for participants supporting penalties by default; but in their study, ordering effects would have been able to produce the same finding. In such a scenario, the mistake condition may have successfully pushed participants toward choosing one of the behavioral nudges, while neither the intentional condition nor control condition dissuaded people from selecting the first option they saw – i.e., the option that was displayed at the top of the list (to increase penalties). In contrast, in our replication, we shuffled the options in order to rule out order effects as an explanation for these results.

Although this was not mentioned in the original paper, certain biases may have contributed to some of the findings. One potential bias is demand bias, which is when participants change their behaviors or views because of presumed or real knowledge of the research agenda. With additional background information (compared to study 3), there may have been more of a tendency for participants to answer in a way that they believed that the researchers wanted them to. In the mistake condition, in particular, since participants were asked about how to reduce failures to appear immediately after being asked why someone would forget to attend, they may have guessed that the behavioral nudges were the responses that the experimenters wanted them to choose.

The higher rate of behavioral nudge support in the mistake condition could also be at least partly attributable to social desirability bias. Social desirability bias occurs when respondents conceal their true opinion on a subject in order to make themselves look good to others (or to themselves). Participants in the mistake condition may have been reminded of the possibility of people not attending court due to forgetting, and may have selected a behavioral nudge in order to appear more compassionate or forgiving of forgetfulness (even if they did not support behavioral nudges in reality).

Conclusion

We gave studies 3 and 4 of this paper a 4/5 Transparency Rating (rounded up from 3.875 stars). The results from both studies replicated completely, supporting the original authors’ main conclusions. We think that there was room for the authors to be clearer about other interpretations of their data, including the possible influence of social desirability and demand bias, as well as their belief that their results may change over time.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the original paper’s authorship team for their generous help in providing all necessary materials and providing insights prior to the replication. It was truly a pleasure to work with them. (However, the responsibility for the contents of the report remains with the author and the rest of the Transparent Replications team.)

I also want to especially thank Clare Harris for providing support during all parts of this process. Your support and guidance was integral in running a successful replication. You have been an excellent partner. I want to thank Amanda Metskas for her strategic insights, guidance, and feedback to ensure I was always on the right path. I want to finally thank Spencer Greenberg for giving me the opportunity to work with the team!

Purpose of Transparent Replications by Clearer Thinking

Transparent Replications conducts replications and evaluates the transparency of randomly-selected, recently-published psychology papers in prestigious journals, with the overall aim of rewarding best practices and shifting incentives in social science toward more replicable research.

We welcome reader feedback on this report, and input on this project overall.

Appendices

Study 3 full table of results

| Hypotheses | Original results | Our results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participants have lower support for using behavioral nudges to reduce failures to appear for court (Mcourt) (described in a hypothetical scenario) than for using behavioral nudges to reduce failures to attend other kinds of appointments (Mother) (described in four other scenarios). | Mcourt = 43% SD = 50 Mother = 65% SD = 34 paired t-test t(300) = 8.13 p = 1.141E −14 | Mcourt = 42% SD = 50 Mother = 72% SD = 32 paired t-test t(393) = 12.776 p = 1.669E-31 | ✅ |

| Participants rate failures to attend court as being: (1) less likely to be due to forgetting and (2) more likely to be intentional, compared to failures to attend non-court appointments (captured in four different scenarios). | (1) Less likely forgetting: Mcourt = 3.86 SD = 2.06 Mother = 4.24 SD = 1.45 paired t-test t(300) = 3.79 p = 1.837E−4 (2) More likely intentional: Mcourt = 5.17 SD = 1.75; Mother = 4.82 SD = 1.29 paired t test, t(300) = 3.92 p = 1.083E−4 | (1) Less likely forgetting: Mcourt = 3.23 SD = 1.85 Mother = 3.74 SD = 1.43 paired t-test t(393) = -7.057 p = 7.63E-12 (2) More likely intentional: Mcourt = 4.97 SD = 1.80 Mother = 4.49 SD = 1.41 paired t-test, t(393) = 6.30 p = 8.246E-10 | ✅ |

Study 4 full table of results

| Hypotheses | Original results | Our results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Participants are no less likely to support behavioral nudges in the “control” condition compared to in the “intentional” condition. | Control: 63% supported nudges Intentional: 61% supported nudges χ2(1, N = 304) = 0.09 p = 0.76 | Control: 64% supported nudges Intentional: 69% supported nudges χ2 (1, N = 440) = 1.090 p = 0.296 | ✅ |

| (2) Participants are more likely to support behavioral nudges in the “mistake” condition than they are in the “control” condition. | Control: 63% supported nudges Mistake: 82% supported nudges χ2(1, N = 304) = 9.08 p = 0.003 | Control: 64% supported nudges Mistake: 88% supported nudges χ2 (1, N = 441) = 34.001 p = 5.509E-9 | ✅ |

| (3) Participants are more likely to support behavioral nudges in the “mistake” condition than they are in the “intentional” condition. | Intentional: 61% supported nudges Mistake: 82% supported nudges χ2(1, N = 304) = 10.53 p = 0.001 | Intentional: 69% supported nudges Mistake: 88% supported nudges χ2 (1, N = 433) = 23.261 p = 1.414E-6 | ✅ |